Fast fashion, the problems and the opportunities

The end of fast fashion?

Fast fashion has become a staple part of our retail landscape. Shoppers have developed a seemingly insatiable desire for new clothing, retailers have responded by providing an ever-changing range of fashion at cheap prices, and this in turn has fed and stoked the desire further. As a result, in the past 15 years clothing production has roughly doubled. It is a trend seen globally, and in the UK alone we consume 26.7kg of new clothing per capita – the highest consumption rate across Europe.

Yet this seemingly unstoppable insatiability for new cheap clothes may be coming to an end. Concerns grow around the environmental impact of fast fashion, as does awareness of the forced and child labour that has often been involved in the creation of fast fashion. In this article we take a look at what is going on and what it means to the retail industry. Are we witnessing the end of fast fashion? We take a look at how retailer can adapt, where there are opportunities, and what retailers can do to get ahead of the curve and to cement brand loyalty.

Environmental factors

Over the past few years, awareness has grown around the environmental impact of the fast fashion industry. High profile figures such as David Attenborough, who at the United Nations’ sponsored climate talks announced that climate change was “our greatest threat in thousands of years”, and that “we are facing a man-made disaster on a global scale”, have woken our awareness to how our choices as humans are impacting the planet.

And with fashion being the second biggest polluting industry after oil, it is no wonder that scrutiny has befallen the retail industry. 1.2bn tonnes of carbon emissions is produced by the global fashion industry every year – this is more than the emissions of international flights and maritime shipping combined. And at the current rate of consumption, textile production will account for 25% of all global carbon emissions by 2050.

Fabric and clothing production uses a huge amount of water – one cotton t-shirt alone uses 2,700 litres (this is the same as an average person drinks over two and a half years) – and can result in extensive water pollution. Countries heavily involved in clothing production, such as India, China and Pakistan are also more likely to suffer severe water stress and scarcity.

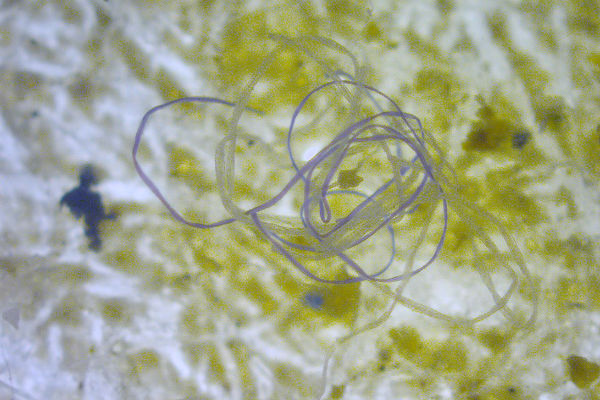

But what has perhaps shocked consumers even more is the realisation that the impact of each garment goes far beyond its production. 700,000 fibres of synthetic materials are released with every single wash. Half a million tonnes of microfibres reach the ocean every year. Marine habitats are being polluted and these fibres are being eaten by fish and entering our food chain.

Ethical factors

To keep up with our demands for fast fashion, Remake estimates there are 75 million people around the world making our clothes, and 80 per cent is made by women aged 18 to 24. Reports of forced and child labour are rife in countries such as India, Philippines, China and Vietnam. In Bangladesh, garment workers are paid around $96 per month, while the Government’s wage board reports that wages need to be three and a half times that amount to enable a ‘decent life with basic facilities’.

Documentaries such as ‘The True Cost’ and Stacey Dooley’s ‘Fashion’s dirty secrets’ have increased awareness around the impact of fast fashion on the lives of workers around the world, and called in to question the ethics of the choices we are making in the western world.

Social Factors

This links in to both the environmental impact and the ethical considerations. But the shocking truth is that we don’t even wear a lot of the fast fashion we buy. The clothes are being produced at great cost to the environment and to the lives of workers, to then sit in our drawers and wardrobes unworn.

In the UK alone, we have £10bn worth of clothes that we do not wear. That is £200 worth of stuff each. Hundreds of thousands of tonnes of clothing are thrown away each year – one rubbish truck’s worth a second – with 80 per cent of this ending up in landfill. And clothes that end up in landfill can take up to 200 years to degrade.

As consumer’s awareness and understanding grows around the impact of our purchasing choices, the feasibility of fast fashion increasingly falls in to question. Is this the beginning of the end for fast fashion?

Change is coming

Sustainability

According to research from fashion search engine Lyst, in 2018 searches for ‘sustainable fashion’ increased by 66 per cent, while page views for ‘sustainable denim’ were up by a huge 187 per cent. What this demonstrates is that shoppers are still looking to buy clothes, but, with growing awareness of the environmental impact of different fabrics and the ethical implications of garment creation, consumers are being more careful about the fashion they purchase.

GlobalData found that 64 per cent of UK consumers say they consider the impacts on the environment in their choice of retailer and products when buying clothing and footwear, and this rose to almost 70 per cent for those under the age of 34.

In response to increased consumer pressure for sustainability you will find statements of intent and action on most large UK retailer’s websites, retailers are developing new sustainably-sourced ranges, and within the store are prominently promoting their use of ethical fabrics on key items.

Resale

Consumers are increasingly turning towards second-hand clothes as a way to satiate their desire for clothes. Buying one used item reduces its carbon footprint by 82%, reports research firm Green Story Inc, so it is easy to see why many consumers are turning towards this as an alternative to buying new.

GlobalData reports that over the last three years the fashion resale market has grown 21 times faster than the retail market. Resale often focuses more on high-end second-hand items, rather than the typical charity shop ware we see on the high street. Currently most resale is found online. Vinted is one such site, with 11 million members and selling an item on average every 49 seconds. Resale is big business.

The popularity of resale hasn’t gone unnoticed by traditional retailers – 9 out of 10 retail execs now say they want to enter the resale market by 2020 and we anticipate this will spill out of the online arena and on to the high street very soon.

Recycle

60% of shoppers say they would increase loyalty to a brand if a recycling programme was offered, and in response, on the high street many major UK retailers have launched schemes that allow customers to return worn clothes they have previously purchased from the store. Schemes vary but essentially shoppers return their unwanted items and may receive a small payment or, very often, a shopping voucher. The aim is to reduce the amount of old clothes going to landfill and to maximise the value of every item of clothing produced.

Shoppers are keen to take advantage of these schemes, Marks & Spencer’s ‘schwopping’ scheme has prevented more than 7.7 million items of clothing from being thrown away since it launched in 2012.

Rental

Pioneered back in 2009 in New York, Rent the Runway offers customers the chance to rent rather than buy clothes. Whilst we may be used to being able to rent dinner suits, hats and ball gowns, renting everyday clothes is a relatively new concept but one that consumers are increasingly turning to. New stores are coming online, such as YCloset, that as well as offering one-off rentals customers are being offered subscription packages that allow them to rent a number of items each month for a flat monthly fee. It is like Netflix for clothes.

Currently most of this activity is online, but similarly to the resale market, I think it will only be a matter of time before we see clothes rental stores on our high streets; perhaps even rental options within our existing major retailers.

The benefit for lovers of fast fashion is clear. They can still get new items as often as they like, but without the heavy cost to the environment as items are returned for someone else to wear rather than sitting unwanted in the back of the wardrobe after a couple of times being worn. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation calculated that if you can double the number of times you wear a garment, you decrease the environmental footprint by 44%, so renting clothes makes sense if you still want regular new clothes but without the environmental price tag.

What else can the high street do?

We mention above that retailers are developing new ranges using sustainable and responsibly sourced materials. Consistent marketing around these ranges will help further raise customer awareness and boost sales of these clothes. We wrote a while ago about Matalan and how their consistent marketing through from the catalogue to the signs in-store help customers make clear decisions, and the same principle applies to these new, specially created ranges of sustainable clothing. Consistent marketing helps guide the customer through from the initial thought to the final purchase.

Designating specific areas within the store can also help people navigate to find the items they are looking for, and using point of purchase (POP) will help draw the attention of browsers. Clear signage is a must.

Customer education is also important and something retailers need to consider. In the same way that we have come to realise that cardboard is not always the better environmental choice over plastic, some fabrics, like cotton for example are not always the best environmental choice due to the amount of water and chemicals involved in its development. The complexity and ambiguity make it hard for customers to make quick, easy decisions when making purchases. I wonder if in time, we will see a traffic light system similar to what we see on foods where the levels of salt, sugar etc are listed and colour coded; perhaps we will see key production criteria broken out on each clothes item so customers can be fully aware of the environmental impact of the clothes they are buying. For now, however, retailers can help their customers by giving them information about the different types of fabrics and the production methods involved to help them make informed decisions.

High street retailers have a huge advantage of being ‘there’. Shoppers can go in to the store and feel and see the clothes for themselves. They can talk to staff directly and have their questions answered. Retailers can build on this potential by offering shoppers ‘extras’ that their online counterparts cannot compete with. In addition to the clothing recycling bin schemes that many high street shops offer, how about workshops where customers can get ideas of how to mix and match their old clothes with key sustainable items of new stock, or upcycle sessions where people are shown how to make simple adjustments to their old clothes to turn them in to something new. Jeans become shorts, a skirt becomes a bag, and so forth. Having the customers coming in to the stores gives the high street a real advantage that they can maximise and build customer loyalty at the same time.

So, is it the end for fast fashion?

I think what we are witnessing is not the end of fast fashion but the transformation of fast fashion. Old habits die hard. People like a fresh wardrobe with new choices and new styles. But how we produce these clothes, what people choose to buy and how they buy these clothes is changing. As awareness builds around the environmental and ethical impact of clothing, we are witnessing the beginning of huge changes in the fashion industry and in customer preferences, retailers that act now will get ahead of the game and cement loyalty with their shoppers to ensure they thrive in this new shopping climate.

Key takeawayAs environmental and ethical understanding grows, the fast fashion market is changing. Rental and resale options are providing consumers with new ways to shop and as these sectors grow we expect to see them enter our high street as physical stores. Consumers are moving away from the cheap, throw away clothes traditionally associated with fast fashion, and looking for garments that are affordable but with accountability in terms of the fabric and production methods. And retailers are responding to this demand with new ranges focused on sustainability, as well as in-store clothes recycling schemes. Fast fashion as we have known it may cease to exist but the market for new styles and fashion won’t abate, and retailers will continue to evolve and respond to meet customer demands.

Image attributions:

- Microplastic fibers By M.Danny25 – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0

- Sweatshop by Marissaorton from the sweatshop project image credit | licence | no changes apart from resize and cropping